Francesco Cacciatore describes himself as a skeptic. After spending two decades in the European aerospace industry, he reached a personal crisis that led him to make an undeniably optimistic bet: he started a space company. He recalls asking himself what he was doing with his life. Despite receiving interesting job offers, he realized he wanted to build something himself.

That something became one of the most difficult challenges in aerospace: reentry. Together with his cofounder Víctor Gómez García, Cacciatore established Orbital Paradigm, a Madrid-based startup focused on building a reentry capsule. The company aims to unlock new markets for materials manufactured in zero gravity.

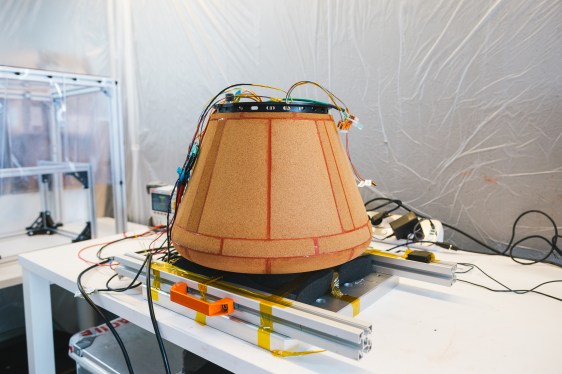

In under two years, and with a team of nine and a budget of less than one million euros, the company constructed a test capsule named KID. This hardware serves as a precursor to a future reusable capsule called Kestrel. The KID capsule is deliberately minimal, weighing about 25 kilograms and measuring roughly 16 inches across. It has no propulsion system. This mission will mark the first time the startup places its hardware in orbit.

The customers for this initial demonstration include French space robotics startup Alatyr, Germany’s Leibniz University Hannover, and a third unnamed customer. To date, Orbital Paradigm has raised one and a half million euros in seed funding from investors Id4, Demium, Pinama, Evercurious, and Akka.

The company did not originally plan to develop return capsules. The cofounders first envisioned working on in-space robotics. However, prospective customers consistently said their real need was a capability to go to orbit, remain for a short time, and return safely—and to do so repeatedly.

Cacciatore observed that customers do not want a one-off mission. Institutions, startups, and companies frequently want to fly between three and six times per year. The biotech industry represents a particularly lucrative market because microgravity can enable breakthroughs in new materials, drugs, and therapies. These applications often require repeated tests by their very design.

This market insight led Orbital Paradigm to build a smaller capsule rather than a large vehicle like SpaceX’s Dragon. Cacciatore explained that if you want to fly hundreds or thousands of kilograms, your customer is no longer the payload but the destination itself.

The market for orbital return is becoming more crowded on both sides of the Atlantic. Varda Space Industries became the first company to achieve a commercial reentry in 2024. Europe’s The Exploration Company successfully completed a controlled reentry with its own test vehicle this summer.

American startups like Varda and Inversion Space benefit from unique advantages. Notably, the Department of Defense and other agencies have invested millions into hypersonic testing and delivery demonstrations, often through non-dilutive funding like grants or contracts that do not require giving up company ownership.

Cacciatore acknowledged that his company does not have access to the same support. This is one reason why Orbital Paradigm builds to sell to customers from the very beginning. He stated that European startups are starved for such funding and therefore need to be more athletic in their approach.

The first launch is rapidly approaching. Orbital Paradigm will fly its maiden mission in approximately three months with an unnamed launch provider, carrying three customer payloads. The KID capsule will not be recovered. The mission goals are to separate from the rocket, transmit data from orbit, survive the intense heat and speeds of hypersonic reentry, and ping home at least once before the capsule impacts in an undisclosed area.

Cacciatore noted that the vehicle was designed specifically so it would not have to land in a precise location, which reduces both cost and complexity.

A second mission is planned for 2026. It will feature a scaled-down version of the Kestrel capsule, equipped with a propulsion system and a parachute to guide it to a landing in the Azores. Portugal’s space agency is developing a spaceport there. Unlike the first mission, this one will have no orbital phase. The capsule will launch, spend about thirty minutes in microgravity, and then return. For this mission, the company will be able to recover both the vehicle and the customer payloads inside.

Cacciatore expressed pride in what his team has accomplished so far, but he remains clear-eyed about the challenges ahead. He stated that until they actually fly, they haven’t done much. Words are nice, but flying is the ultimate test.