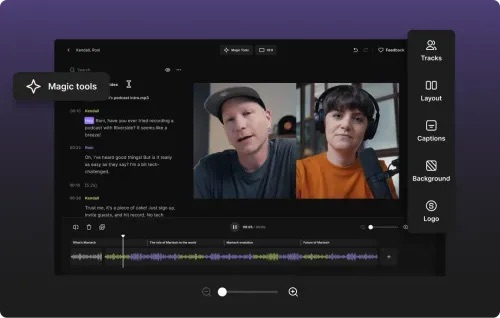

The online podcast recording platform Riverside recently released its own version of a year-end review similar to Spotify Wrapped. This recap, called Rewind, creates three custom videos for podcasters. Instead of sharing basic statistics like recording minutes or episode counts, Riverside compiles a fifteen-second collage of laughter, showing a quick succession of clips where my podcast co-host and I make each other crack up. The next video is similar, except it is a supercut of us saying “umm” repeatedly.

Then, Riverside scans its AI-generated transcripts of your recordings to find the single word you said more than any other, presumably filtering out common words like “and” or “the.” It is a bit ironic, but on my podcast about internet culture, my co-host and I said “book” more often than any other word. This was likely skewed by our subscriber-only book club recordings and the fact that my co-host has a book coming out, which we mention frequently.

Another show on our podcast network, Spirits, said “Amanda” more often than any other word, not because they are obsessed with me, but because they also have a host named Amanda.

In our podcast network’s Slack, we exchanged our Rewind videos. There is something inherently funny about a video of people saying “umm” over and over. But we also know what these videos represent: our creative tools are becoming more saturated with AI features, many of which we do not want or need. The Riverside Rewind points to the uselessness of these tools themselves. Why would I need a video of my co-host and I saying the word “book” over and over? It is good for a quick laugh, but there is no substance.

Though I enjoyed Riverside’s AI recap, its arrival comes at a time when my industry peers are losing opportunities to create, edit, and produce new podcasts, thanks to the same AI tools that generated our Rewind videos. But while AI allows us to automate away some tasks, like editing out our “umms” and dead air, podcasting itself is not that mechanical.

AI can quickly generate a transcript of my podcast, which is important for accessibility reasons, helping to automate an activity that used to be incredibly time-consuming and tedious. However, AI is not able to make editorial choices around how to maneuver audio or video to tell a story effectively. Unlike the human editors I work with, AI cannot determine when a tangential conversation in a podcast is funny and when it should be cut because it is boring.

Despite the rise of personalized AI audio tools, like Google’s NotebookLM, its ability to serve as a creation tool has also seen high-profile failures lately. Last week, The Washington Post started to roll out personalized, AI-generated podcasts about the news of the day. You can see why this would seem like a good idea to profit-hungry executives. Instead of paying a team to do the intensive work of researching, recording, editing, and distributing a daily show, you could automate it, except you cannot.

The podcasts spouted made-up quotes and factual errors, which is existentially dangerous for a news organization. According to reports, the Post’s internal testing found that between 68% and 84% of the AI podcasts failed to meet the publication’s standards. This seems like a fundamental misinterpretation of how large language models work. You cannot train a large language model to distinguish reality from fiction because it is designed to provide the most statistically probable output to a prompt, which is not always the most truthful output, especially in breaking news.

Riverside did a great job making a fun end-of-year product, but it is also a reminder. AI is infiltrating every industry, including podcasting. But in this moment of the AI boom, as companies tinker with new technology, we need to be able to distinguish between when AI serves us and when it is fodder for useless slop.